Dream Catcher

To Die Next To You BY Rodger Kamenetz

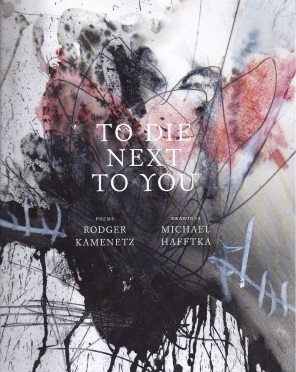

Published by Six Gallery Press. 99 pp., $19.95

REVIEWED BY Jordan Soyka

To Die Next To You starts at the beginning, referencing the creation myth in Genesis; in the first poem, (ironically, "After After") Rodger Kamenetz writes, "But if you would apply hand to heart / kiss to brain, tohu to bohu, / I would be astonished and the void would be blue." "Tohu wa bohu" is part of the line from Genesis commonly translated as "Let there be light." However, the phrase specifically means 'waste' or 'void,' and points to the complex, dependent relationship of form on chaos & nothingness.

As a poet, bringing creative structure to the bedlam of inner emotion and thought, this is a relationship Rodger Kamenetz is intimate with--To Die Next to You is Kamenetz's sixth book of poetry. However, the binary of form & chaos is only one of many that are disrupted in the book's poems. These disruptions (indeed, the impetus of the book) are intimately tied to Kamenetz's study and practice of archetypal dreamwork.

Kamenetz started drafting these poems in 1999, when he began his initial dreamwork with Marc Bregman, master teacher at North of Eden; he continued writing them until 2004, when he set the manuscript aside. The concept of dreams complicates the relationship between void and form. Certainly our dreams are influenced by our daily lives, but when one is intensely studying those dreams for meaning, guidance, even transformation, the dreams are as much cause as effect-the chaos in each (our lives, our dreams) gives way to form in the other. Moreover, the ultimate goal of dreamwork is "death to self," a painful and transformative process that involves shedding former identities and attachments. Though dreamwork itself is not the poems' direct subject (the book reflects on everything from New Orleans to Jerusalem, the everyday to the metaphysical) the transformative lens that comes from dreamwork unites the book's poems by upending binaries related to sign & siginifer, past & present, and life & death.

One of the first breakdowns we see in these poems is that of signification. For instance, the line between sign and signifier is blurred in "After After," when Kamenetz writes "I saw the word poetry cover poetry. / I saw the word snow and saw snow." In the second of those lines, we assume the speaker imagines snow (rather than literally seeing it) when he sees the word, but the use of "saw" in both clauses undercuts the distinction between imagination and reality. Moreover, language giving way to sensory experience is an inversion of the way we normally imagine that process, and the fact that both seem to happen simultaneously (seeing 'snow' and seeing snow) breaks down the distinction between language and the world. The first line is even more complex; because poetry is made up of words, it's puzzling to imagine a word covering poetry. The suggestion is that poetry itself is more than (or perhaps even separate from) the words that comprise it (or perhaps it's a clever joke about looking at the latest cover of Poetry magazine.). In "Conversation Stopper," a poem about a dinner party, the line between sign and referent is obliterated completely when a woman at the party tells everyone, ".I believe this reality / is a symbol-every moment is a symbol / . / just as much as if this were a dream."

The concept of history is also complicated by many of these poems. Three of the book's poems have the word 'after' in the title ("After After," "After the Storm: A Brick as Fragile as a Dream," and "After the Flood"), and Kamenetz once commented that poems are always coming after something, speaking to the importance of poetry as witness, but also, perhaps, to a frustrated view of poetry as somewhat impotent-a 'response to' rather than an 'instigator of.' Indeed, "After the Flood," seems to be about the aftermath of Katrina-the "ruptured facades" of the "houses [that] were built on mud" and the "Shadows [that] crawled back into broken locks" when "the waves receded to the center." In "After the Storm" we see dangerous effects of the city's destruction on the bodies of those left (as the dust of wrecked buildings "coats" "the sponge of the lung"), as well as their psyches (".If you find an old bone, / Be sure it's not canine before you call 911.").

Ironically, however these poems were written several years before Katrina, complicating the gap between prophecy and witness. Indeed, the poems suggest the dangers of chronological history, in which the past becomes an object of obsession. This is certainly true in "The History of Today," wherein the speaker sees history (in this case, Jewish history) as alienating: "I was born only to have this past," the speaker tells us [my emphasis]. "My mother taught me to worship it... So I was left alone in the temple, with the candles blown out and the incense of old spoiled prayers."

Though Kamenetz obviously couldn't have predicted Katrina, the fact that the poems existed before the storm offers an alternative vision of history similar to Indra's Net; the various points of history are not chronological, but a complex web, each nexus reflecting every other. Both the past and the future exist on the same plane, and this realization is a transcendent and poetic one:

There is a rose in the garden, an eternal rose In the mind. There's Dante's rose in paradise, angels Singing in the folds of the rose. All of these roses are one. ("Rose on Rose")Thus, poetry, as a space of both creation and recollection, projection and reflection, is perhaps the ultimate historical nexus.

Strikingly, the poems in To Die Next to You are accompanied by drawings from Michael Hafftka, and the interaction between the poems and the art raises further questions about cause and effect in the creative process. To create the drawings, Hafftka's wife would recite one of Kamentz's poems over and over while Hafftka sketched. And although Kamenetz didn't edit the poems (which preceded his even meeting Hafftka) in response to the art, the writing and drawings interact in much the same way Rodger's dreamwork influenced his writing process. Certain abstract ideas are reified in the poems. For example, in "The Miner's Song" (a metaphorical poem about gold mining), the overwhelming feeling as we follow the speaker "Miles and miles below the ground" is one of claustrophobia and utter dependence: "We were provided with bread, / Provided with sleep. A dog was provided / To taste the oxygen." The drawing on the opposite page is a body against a gray background; the body has two sets of overlapping legs, as if it's trembling or going in & out of focus; and where the head should be, there's a splatter of black ink. Thus Hafftka takes the obliteration of identity at the heart of the poem and makes it literal. As a result, the poems, are themselves transformed by the dialogue that erupts. As Kamenetz said while performing a reading from the book, "The poems are reading the paintings and the paintings are reading the poems."

The paintings, themselves, seem rather dark-violent and spattered. The abstract drawings are imposing and chaotic, and in the figurative drawings, the bodies are contorted and vulnerable. However, there are also bright splashes of warm color, suggesting a more complex vision. For instance, in "Conversation Stopper"-a poem about a moment of transcendence-we see two bodies facing each other. Both lack any definition in the legs and torso, and one has basic facial features while the other face is scratched out in black ink; nonetheless, both figures are bowing their heads so that their foreheads are touching, and a yellow glow surrounds the bodies.

As Kamenetz said during a recent reading, whether something is 'dark,' "depends on how well-adjusted your eyes are." The violence and chaos in many of the drawings may signify the (equally violent) transformations that occur in the poems. In "Stink Horn," Kamenetz recalls the day his friend Alex Smith dug up a stink horn mushroom, and placed it, "nestled in dirt and moss," in a shoebox by his window. "Two days later, a shaft / Popped out through the shred hymen / With a glistening white net of yarn." The imagery, though violent and sexual (more so since the stinkhorn's scientific name is Phallacae), is ultimately about birth. But in the next line, the mushroom emits "a perfume that stank of death," and is devoured by flies. The mushroom dies (as does Alex), but the poem ends with Kamenetz imagining the invisible spores on the flies' feet-a vision of rebirth.

Similarly, "Dig Dug" begins, "In the broken line that threatens the sidewalk, / In the tunnel in the bark, I ate my way with worms," and we follow the speaker as he works through the dirt and clay, even "[breaking] off a finger to dig with," until "A shadow opened, the tunnel moved." The previously suffocating imagery opens up ("There you stood smiling, your whole / Face a moon in telescope glass, big as a lion's"), and the drawing that accompanies the poem seems equally transcendent, with a female form rising out of inky clouds into a golden halo that recalls images of the Virgin Mary. But transcendence is, by definition, too much, and the apparition, "Larger than expectation.," is too much for the speaker-".bursting veins & chambers / In the claptrap purse I used to call my heart." Transcendence is radiant obliteration; the phrase "I used to call my heart" suggests that even the most fundamental significations be done away with in the new realm the speaker finds himself in.

This is the crux of all the inversions in To Die Next To You-during the writing of these poems, Kamenetz was trying to achieve what the Sufis call "Dying to Self" (the ultimate goal of dreamwork therapy) in which one must cast off all former attachments and identities in order to be 'reincarnated' within this lifetime. Such a transformation renders all binaries moot.

It's a difficult and painful journey, as laid out in the final two poems of the book: "The First Time I Laid Myself Out Open to an Outside Physician" and "Half Accident." "The First Time" begins: "There was an appointment book in hell. / All the devils were laid out like smoke, / Thousands seething like foam on gums." The speaker chooses to take this "appointment;" in the process, he loses his identity ("When I heard my name called it was a vowel, not a word") and opens himself up to all sorts of agonies. There is a transformation at the end of the poem, but not one that's simplistically triumphant-"I was on my own. I was getting along already." Again, we see an inversion-the speaker seems to be just starting his journey at the end of the book. Similarly, "Half Accident" offers no final transcendence; instead, it's a cautionary tale. The speaker in the poem has been disassembled-"He lay with his arms out, teeth in a tin dish his blood in a bowl. / The limbs were arranged side by side, fingers, in the sockets five and five"-and is on the verge of transcendence (i.e. death). But in a darkly comic twist, the speaker refuses to cross over ("I'm not dead at all, the patient shouted back, I'm undecided in everything like dying") and leaves the doctor's office with his body jumbled, like a grotesque Mr. Potato Head.

The poems in To Die Next to You are an account of Kamenetz's own transformative journey. But it's a transformation that's continually blooming; the poems themselves have transformed through Hafftka's drawings, and the poems invite the reader, too, to join in the journey:

And if I traveled through the darkness

You sent me as a guide,

Would you meet me where the burning

Makes new light for the sun?

It's an open invitation. But the impetus is on us; the world moves on, with or without us-"The universe began an instant ago. / And went..."

END