|

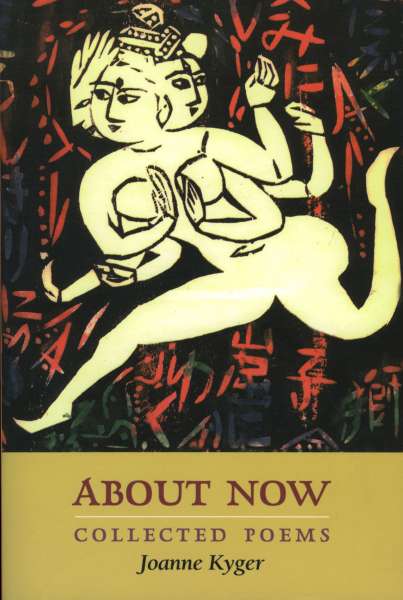

About Now: Collected Poems

By Joanne Kyger

Review by Stephen Vincent

National Poetry Foundation

798 Pages; $34.95

Joanne Kyger's accumulated work is mammoth and resists either quick reading or an over-reaching statement of its full worth. Her extraordinary use of words provide the way in which an unfolding universe finds multiple, diverse, both contrary and momentary, means to resolve. Language is most definitely at the heart of her making. To be overtaken by this large volume, and then be asked to review it, is no mean task. This gathered history of "Now-ness" is persistent, unflagging from Joanne's first poems, 1957 up until 2004, a product of a calling that, no doubt, surely she continues and we are delighted to receive.

Possessed of what Joanne calls a 'raw nervous energy', from early on it's a voice called to communicatus, whether it's the seed that feeds the sparrow in her backyard, or the stumbling, sometimes goofy, then joyous, if not vexatious and/or loving camaraderie of poets, artists and neighbors in Bolinas, her home for forty years on the Pacific, just north of San Francisco. This is an eye and ear, and a reader that examines, vertically and horizontally, ways in which to use the poem — its potential proportions, shapes and sounds — as means to articulate the depths and heights of whatever is to be discovered in immediate territory.

Stroke of brush in painting

Pitch of tone in writing...

December 7, 2004

p. 743

As evident in the work, Kyger clearly went through a long period of initiation in order to take on the position, power and full calling of being a poet. As the poems in the volume evolve there is no question of her rising to the calling. As to the initiation part, many of the book's early poems San Francisco in the late 50's and 60's are written with satiric, hilarious and biting humor, and are affectionately aimed at her 'colleagues' and mentors, particularly Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan. Under her pen, each falls flip-flop to the mat even while still guiding her to pay close attention to the sound and lay of the language as it makes way across the page. Wonderfully revelatory are her accounts in the Dharma Committee Newsletter — essentially a bulletin for a gang of younger, fellow poets — on what it was like to actually break through and find position in this world of self-entitled poet giants and teachers. In a sweetly ironic 1958 note on Robert Duncan's workshop of mostly men at the SF Library, she recounts:

It was suggested by Robert Duncan that we all write Cock Poems for the next class. Splendid! (p. 386)

In the Newsletter we meet her early peers - including George Stanley, Joe Dunn and Harold Dull among them — and early on we get her sense of both pleasure and comedy in being part of a community:

. . . .H(arold) Dull discovered a new way to entertain himself: talking to Tom Field while seven people push H. Dull's car halfway to North Beach because it won't start at 3:30 A.M. Harold sits very nicely in his convertible, proud and erect…oblivious to the gasps of seven throats and pound pound pound of 14 feet and the dilating throb of pupils. Tom said that he didn't agree with everything Harold had to say but after he had run fifteen blocks, his nose abreast of the windshield wiper he started wondering what this was all ABOUT…

This early Marx Brothers kind of humor will continue to stick with Joanne when she moves to Bolinas towards the end of the 60's.

In addition to Spicer and Duncan, her perhaps strongest imprint and particular focus as a writer, it seems clear, comes through her association and travel with followers of diverse manifestations and teachings of the Buddha — poets Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, Lew Welch, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg amongst them. It is the East that enfolds her and, ultimately, provides the poems with their larger sense of comedic theater and religious grace. The theosophic forces, including writings and art of India, Burma, Tibet, China and Japan, as well as, ultimately, Western 'transmitters' such as Madame Blavatsky, become the divining rods that feed her method and shape her attention. Reading her work makes it clear that behind the seeming simplicity and language of the poems, there has been a large amount of study and sympathetic intuition. Which is in no way to discount her very real knowledge of traditions of Anglo-American verse. In fact, one way to read the work, in part, is as a unique, creative reconciliation of these two distinctly different traditions – a purpose that she shares with her peers and mentors including Kenneth Rexroth, Whalen, Snyder, Welch, Ginsberg and Kerouac.

Yet, no matter the genealogical umbrella of associations for this work &mdash the desire "to harmonize with the Divine" and the initiation to become articulate as such — is a calling that remains personal and required no small sacrifice:

. . . I do not want to say

he is dead yet because he has not come back, but my

sadness for the missing comes recognized, is acceptable.

Gone with the last look he questioned me with. Have you

done this to me?

Indeed are they my forces or the forces

I am within. That no children come from me to love. And I

am this space in time, this focus of articulation, that hears

the bee buzz around and around. (p. 277)

But story, such as it is, is implicit to tracing, hearing and interpreting the work in About Now. I don't think it is an easy story. Indeed it has the pioneer edges of anybody at work at becoming genuinely settled in America, a land in which the majority of us are not indigenous, and our 'claim' here is fraught with bad history. So it is interesting to see the way — the graph of the way — in which Joanne takes up Bolinas, once a colonial port, touched early on by Sir Frances Drake:

...but none of it 'indigenous' to here except

through conviction of the poet combining

these strands into a useful cord, a thread

to throw into the dream and see it

come up clear

as a picture in the evening.

From "The Fog is halfway over the mesa" (p. 719)

As if in the role of Penelope in the 60's and 70's — whose Odysseus is off plundering and screwing up Viet-Nam — the work goes humble to gather and weave the residual strings in the local world — an impulse perhaps similar to Charles Olson in Gloucester. In particular, as C. Hart Merriam, the turn of the last century anthropologist before her, she re-articulates — from which I will not quote — the remains of Miwok fables, the long vanquished tribe that surrounded Mt. Tamalpias, the mountain that overlooks Bolinas, as well as the entire Bay Area.

Indeed, Joanne's work evolves to become the articulate locator, the eye and language of the newly indigenous, that is her friends and neighbors, the poets and the artists that surround the Bolinas lagoon, most of whom are also refugees from other places, other realms. Fragile, full of edges, ambitions or in some cases down right goofy and laid back, she sets to revealing the tale:

There aren't any backrooms out here anyway

in which to make deals

unless they're over the septic tank

but believe you me people are just as shifty

over their septic tanks as they are anywhere else...

from "Whatever It Takes" p. 740

However, what makes the poems interesting is the refusal to yield to pre-conceived narrative. In the manner of meditation, facts and lines (strands) come up — not necessarily in any apparent order — to yield an insight into the substance of things as they are:

I hope this working out as a novel

approach, at least the disruptions make

the substance. Otherwise inside

doesn't make any difference

if I've forgotten anything

As a process, it makes the poems — in whole or in sequence - continuously arresting. The playfulness of the language, the rhythms of its music, provide the poems with a visceral, if not almost athletic sense of engagement, as this, for example, approach to a lover at dinner with whom she has had, earlier in the day, a furious argument — before he stormed off to work without breakfast - about why he was wearing the same shirt for the third day:

. . . . We'll sit at the table, and don't put me on, the room in my heart

gets nourished by your friendly, handsome looks. You read

a lot of books. (p. 317)

That quick shift to the phrase at the end, the rhyme of "books" with "looks" is loaded with a certain bite. The present or 'now' quality is in the layers of images, 'bopping' against each other, then a kind of 'bam' in which a scene is 'undressed' with an insight. Nothing is rarely 'saved' or 'rhetorically secured', indeed it is what it is, not that a particular insight may not elicit a moral rebuke, or an exacting look, an enactment of self-measure. We might be also moved to laughter, lament or the trail of a moon punching light through the window.

. . . . The minister squats down, he has a kilt

on, and you can see his balls hanging there. Thus

clearing up what is under a Scotman's kilt.

(p. 311)

Or:

. . . . The tunes familiar

weeping & laughing

I leave my love behind..."

(pp.209 - 210)

There is a frequent, playful jauntiness to Joanne's work — a delight in play, a kind of let's not only make a party, but let's see what the party reveals. Noticeably it's a party that defies conventional definitions of that term. The party can be between her and the image of the buck in the backyard, the insufferable foggy weather, her domestic partners or the play and/or disputes among any number of friends in the neighborhood. The party in the poem is a way gathering in and crystallizing the parts that combine, dissolve and variously recombine across both private and public worlds. The poems put both poet and community on alert to be alert and not shuck off their part in being present. The reciprocation of one's energy and presence feeds every part — community, poet, and poetry. About Now is not a work — no matter how grumpy Bolinas can be — inclined to hermetic domestic and/or social exile!

I suspect this jauntiness of tone — the willingness to let the poem's tone and strands of language suddenly shift, the juxtapositions of which lead to insights — is what makes the poems keep us on our toes. In a voice much at home with itself, the poems can vary in tone and cadence from a sensual, sacral high toned 17th century hymn to a country and western sassiness. In public readings of her work, this darting, fluctuating tonal quality gives the poem a both earned and exclamatory resolution. If I were to make metaphor here, a Kyger poem can have the quality of a dragon fly — hovering, suspended in the air at one point, quickly diving up or down, and, just as assuredly, turning back in the opposite, or unrelated direction. There are people who can also play the flute like that — sensual, breezy, some times close to shrill and where the clarity of the instrument's notes seem like objects. Here it is in the manner of poetry.

Monday Afternoon May 14, 1984

Now that we have gotten that out of the way

We have a ways to go

to take us thru the time

of this afternoon's wanderings

to the rooms of this house

Two shades of red

matched behind Lyn O'Hare's new painting make it

too busy. The wind

is gusting terribly today. The Pacific Sun's

Lynn Cuncle refers to Bill Berkson's "ramblings

of an agitated mine " in his new book Start Over

Gets me pretty anxious

too. Berserk looking dragon from Nepal gives me

a frenzied stare across the room, as afternoon light

falls thru it.

No birds are out today. Definitely

change Lynn's matting, those reds are chatting up

a storm in the corner. A house is protection today

against all velocity outside going 50 mph.

And this famous wind. It's already dangerous

on 6 0'clock TV tonight.

(p. 459)

To this point I have been writing more of a horizontal world that ranges across a variously appearing and disappearing social and natural world. These poems — especially as the book grows — are infused by the luminosity of what I would loosely call a vertical world. Which is not to say the poems are not also infused by encounters with darkness and absence of light on all levels as one might see those dark hellish figures, for example, on a Tibetan thangka. But more of that later.

However, in some of the most deeply meditative works in this volume, the poems achieve a golden, totally remarkable sense of radiance. Though September has become one of her most familiar poems, I quote it here in full:

September

The grasses are light brown

and ocean comes in

long shimmering lines

under the frost last night

which dozes now in the early morning

Here and there horses graze

on somebody's acreage

Strangely, it was not my desire

that bade me speak in church to be released

but memory of the way it used to be in

careless and exotic play

when characters were promises

then recognitions. The world of transformation

a real and not real but trusting.

Enough of these lessons? I mean

didactic phrases to take you in and out of

love's mysterious bonds?

Well I myself am not myself.

and which power of survival I speak

for is not made of houses.

It is inner luxury, of golden figures

that breathe like mountains do

and whose skin is made dusky by the stars

from All This Every Day (1975)

Not much writing in America, I believe, has achieved this level of what I would call enlightenment. The humble balance of dedication, attention and ravishment infuse the poem in a shape and manner that could never be artificially induced. Indeed, as a reader, I find the work ravishing in ways that cast a spell on my consciousness. This vertical luminous quality — if not necessarily in full form or even directly implied &mdash hovers within and around the edges of much of Joanne's work.

What changes most dramatically as one ends this volume? Ironically what is lost is a kind of innocence about the space of one's immediate world. The delight filled attention to life in San Francisco, Bolinas, as well as the different trips to Mexico, New York and elsewhere finds itself dramatically blown apart. The cause? The arrival and transformation of the entire country by the Bush-Cheney Administration. These are dark, poisonous figures, representative of forces that Joanne is not about to leave unchallenged. An anger is unleashed. The urgency to clarify and cleanse becomes paramount:

. . .What do you see

in the year to come?

"What do I care

about the dreadful karma

about to be disappear

through your kids

who inherit the blood debt

of bombing the cradle

of civilization

into oblivion"

The Psychopath pretends to care

his little prune-face

screwed up

into an approximation

of concern

gargling his speech writers

rhetoric of pre-emption

from "San Francisco

March Against War on Iraq

January 18, 2003"

(p. 732)

Ironically, more than ever in the history of the United States, the world of Tibetan demons — forces of darkness and ravage have penetrated and taken over the country's leadership. For poets and citizens with any political consciousness, it has been a time of either or both paralysis and resistance. For many writers to entirely shut-up and submit to the actions of this Administration is intolerable. In the closing section of About Now, Joanne's most recent work has clearly made a choice to step up to take urgent responsibility that extends much beyond the immediate local – that part of the global party, no matter how horrific, that cannot be avoided.

There is so much more to relish in this volume of which I have no more time to write! For now 50 years (!), Joanne Kyger has brought a singular, yet evolving voice, intelligence and imaginative vision to American writing. As both a poet and longtime, devoted reader of this splendid work, I am sure I speak for many when I express gratitude to the National Poetry Foundation for having brought this wonderful, beautifully edited and designed volume together.

San Francisco

January 2008

|

|