Submissive to everything, open, listening.

No fear or shame in the dignity of yr experience

(Jack Kerouac)

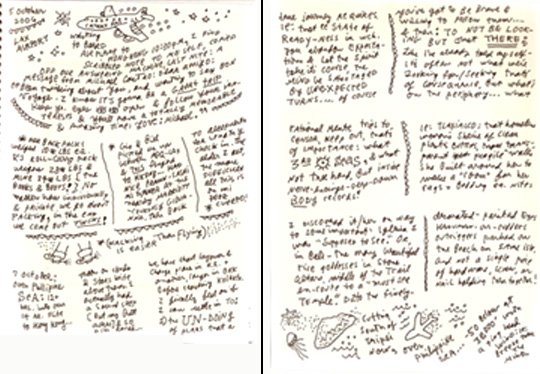

5 October, in flight

Aboard Cathay Pacific across the Pacific, 14-hr flight, 50-below headwinds, to Hong Kong where we'll transfer to a Bangkok flight, then Indian Air to Kolkata. Leaving home, a last-minute phone message from poet Michael Castro: "I know it's gonna be a great trip. Keep your eyes open, follow your interests,

and you'll have a totally memorable and amazing time."

When the 747 reaches stable altitude, I order a cognac and peruse the India guide I've tucked into my pack. It features a "When to Go" section with plenty of advice on weather and festivals, but omits the essential counsel: Go when gusto tweaks, when dreams dictate the journey! I remember the People's Guide to Mexico, a paperback that told you not where to go, what to see, where to stay, but simply how to be. Full of wise and quirky suggestions, it let you roam on your own, free to use your own navigational skills. Chance encounters, serendipity, down-in-the-dirt roll of dice: a better way to go. The guide's long out of print, but good books on regional foods, textiles, music, and architecture abound. Why not take one of these?

The rest will open on its own.

∴

5 October, in flight

L.A. airport check-in was less than amazing. Predictable humdrum of homeland-security personnel coping with rules and regulations that change daily. This time the banned carry-ons were gels, shampoos, liquids, and a few medications. Scissors okay, but not the tiny box cutter I trim news articles with. Just after 9/11 the FBI issued an alert for people carrying almanacs. The reason: "almanacs have statistics, cryptic abbreviations, long-range weather predictions, and particulars of geomancy useful to terrorists." Boarding a flight in San Francisco, my shoulder bag was searched. A Chinese almanac was found, a present from a friend who thought its contents useful for my collages. After prolonged questioning, the almanac was seized, and I got on the plane. But who knows what details under

my name stayed behind on the Fed's computers?

Our most pacifist friend is constantly harassed by U.S. airport security. He's an animal tracker and raptor watcher who often travels abroad. "I'm on a list — pulled out and searched whether my ticket says New York or Mongolia." They're probably spooked because he goes so far and carries so little, can't remember his social security number, and has ripened into old age without ever holding a steady job. He doesn't show up on the screen because he's out of the loop, lives on dried cranberries, walks a thin trail below poverty level. He naps in the grass, has perfected the art of lingering in shady squares among balloon vendors and low-cut señoritas, and is perfectly at home in broken cliffs—thunder his only company. He goes against the American grain by simply doing nothing —in the sense of Po Chü-i's wu wei— non doing / non-interference in the natural course of things. You won't find him wasting time at heaven's gate swinging a pick under any taskmaster's orders. He's got straw between the teeth, bills scattered, rice in the bag, binocs around his shoulders,

and a box of Cracker Jacks. Put him on my list!

∴

5 October, in flight

Renée's carry-on pack weighed 10 lbs, mine 9. Her check-in: 28 lbs, mine 31. No matter how individually we go about planning and packing, in the end we come out twins. Now, 40,000 feet in the stars over Mar Pacifico, I can finally settle into the undoing of plans that a true venture requires; a state of readiness where we abandon expectations, let the spirit take its course, mind sabotaged by unexpected turns. All that's required is willingness to follow them. "Big schemes only bring grief," said Yuan Mei:

Carry only what you need

a light skiff takes the wind

and rides the water lightly.

Part of what I need is a poetry book, small enough to fit the hip. Good poems remind us we all desire nakedness. A moment unveiled in the company of others. To strip, sit at the feast, become new to each other through our work. Why stand in the fashion mall wearing manufacturers' designs? Travel naked! Swim the rain and rivers. With little on your back, amid joys and discomforts, you can wake in the journey, meet other guests, break bread, walk the rooms, ramble the garden. Travel engenders poems, realigns perspective, sure; but mostly it breathes and swells as an end in itself, rich with camaraderie, new views of old cities, fine encounters with flowering slopes in untrimmed backcountry. When Basho wrote:

come see

real flowers

of this painful world

was he not asking poets of all ages (especially the clever ones who seek high profile), to get down off their horses and seek what is low? Beauty in common experience, ache in the plight of the underdog? Nothing hallowed or brainy, just unpretentious images that reveal what convention cannot reach.

red dust

from my notebook —

stars in heaven's stream.

∴

South of Taipei over Philippine Sea. Am I awake inside the dream, or asleep with eyes open? The raw scribble of nerve endings inside my eyelids stops when I catch my head sagging, mouth drooling, flaps down, wheels out. The sky's bright, Hong Kong just below in its hazy nest of hills, choking in pollution-spew from its own upstream power plants. During a brief layover, we sample tea, stretch legs, and buy Chinese remedies from an airport herb shop raising its grate as the sun rises. In a book shop we find Asian publishers selling the same titles we have back home, but far less expensive. Lots of Lonely Planet guides on the racks. But why flood your head with information others deem fit for you? Best to travel the way you'd like to see travel taken. No calculation, no hang up on how others would do it. Tailor the journey after your own heart; keep in mind the worthy forbearers: Basho, Bowles, Eberhardt, Matthiessen, or the late Norman Lewis.

∴

Bangkok. Change planes for Kolkata. Artaud: "I'd like to be bitten by external things, by fits and starts, all the twitching of my future self." Will I be able to write a poem in the past-present of the future-tense in the delirium, grit, and relentless multitude of the subcontinent? The minute we board Indian Air we're in another country. Language, etiquette, gestures change. Saris, forehead tikkas, shalwar kameezes, sugared fennel seeds, spiced tea. Dark penetrating eyes, bright silks, expressive features. A preview of what's to come.

inside uncertainty

a few worthy

lines —

∴

8 October, Kolkata

Wake under ceiling fan whirling at high speed. We're south of the city centre on the bottom flat of Ranjan and Vasudha's apartment, two filmmakers we were put in touch with before leaving home. After a cold shower, swig of mineral water, and fresh set of clothes — the only extra change in my pack—we're timidly out the iron gate onto Sarat Bose, making a quick right around the corner to Rao's South Indian Coffee Parlor. A sign proudly states: WE HAVE NO BRANCHES. The narrow, high-ceilinged interior is milk-white, edged with olive-green. A lazy breeze wafts over marble-topped communal tables from tall shuttered windows accented with burnt-orange. In Santa Fe this would be "chic." Here, just another neighborhood eatery. The cheerful proprietor sits over the morning Telegraph, Hindu deities on an altar behind him. A framed newspaper clipping states that he once held an honored position as a governor's cook. Above, on a shelf, a fat-bellied Ganesha gives a propitious smile,

flanked by two sticks of smoking incense.

The traditional South Indian breakfast — idli, sambhar, chutney, and coffee — is a perfect way to begin our first morning in India. Idli (usually two to a plate) is a miniature saucer-shaped, steamed rice/dal flour pancake. You break it with fingers, dip it into coconut chutney and sambhar served in stainless-steel cups. Sambhar is a hot/sour broth of dal seasoned with tamarind, red chili, peppercorns, curry leaves, coriander, turmeric, cumin, fenugreek, and dry-roasted mustard seeds — light, tasty, and cleansing. Afterwards, we order mishti doi, fresh yogurt sweetened with jaggery, and coffee. South Indians are fervent coffee drinkers and a filtered brew from fresh-roasted beans is a must. Unless you ask — and we don't — it is cut with milk and sugar and comes piping hot in a tiny stainless-steel cup set into a deep saucer. You pour it back and forth, froth,

drink from the saucer, then the cup. A civilized ritual.

∴

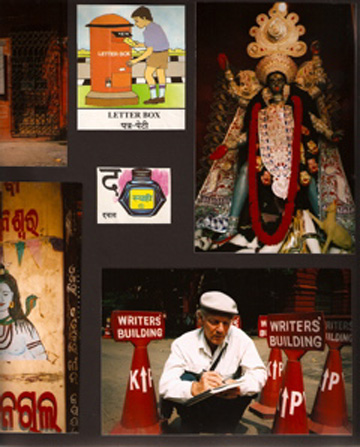

Taxi to Dalhousie Square. It's been renamed BBD Bagh in memory of three freedom fighters martyred for trying to oust Lord Dalhousie. We amble strangely uncrowded Sunday-morning streets, stop before the impressive 1780 red-brick Writers Building, and are at once shooed away for taking photos. The imposing three-story building originally housed British clerks who managed the East India Company's red tape. It's now West Bengal government headquarters and the police are sensitive about it. Colonial-era trading companies abound in this area, faded British churches too. The famous Victoria Memorial we glimpse only in passing: a pompous, bygone palace floating above the Maidan, a two-acre lawn where goats graze and lovers stroll. In January the Kolkata Book Fair takes place here;

the greatest book event on the planet.

Kolkata is book society. Gifts of our own poetry books were well received by Ranjan and Vasudha. Bengalis have high esteem for books. On College Street, one shop after another overflows with literature: Dostoyevsky, Poe, The People's Alternative to Economic Globalization, William Blake, Flora of Karnataka, Emily Dickinson, Subcomandante Marcos, Akhmatova, The Peach Blossom Fan, Ramakrishna, Banking on Biomass, the bandit queen, The Glory of the Divine Mother — bet there's even a People's Guide to Mexico somewhere in the stacks. In Havana we experienced similar bookophilia — strong literary tradition; high regard for poetry and novels. No wonder Hemingway was at home in the Ambos Mundo Hotel, naked at his typewriter, shutters open to the harbor breeze. Cuban poetry readings are still in vogue: not only in book stores, but in bars, tobacco-rolling factories, cement plants, and troubadour houses — free to everyone.

We find a copy of Krishna Dutta's Calcutta, a bit loose at the seams but worth the purchase. In the first chapter, A City Made of Words, she writes: "In Calcutta almost everyone reads some literature and has an opinion of what is good and bad in contemporary writing. Established poets recite to mass audiences, most people can quote poems by Tagore and others. Many Calcuttans compose their own poems for weddings and festivals, have them printed, and circulate them among friends and relations."

The smell of paper is thick along College Street. Musty, yellowed pages. Marbled cardboard. Re-sewn leather. Cracked glue, undone bindings. Moths pressed between letterpress editions of Dante. Silverfish feasting on brittle parchment. Water-stained maps webbed with worm trails. Dust floating on onionskin. Glass paperweights turned amethyst in the sun. Books about to topple from tilted stacks. Shop owners sipping milk tea while balancing overflow stock on the iron railings along the sidewalk: biographies, Sanskrit classics, poetry, children's stories, repair manuals for non-existent automobiles, encyclopedias, religious pamphlets, an 1880s medical volume with tissue-overlaid line cuts of facial tumors, novels, and quirky leftist periodicals of the kind that proliferate in Kolkata's back-alley publishing houses. One shop displays a high-gloss calendar: Saraswati on an open lotus holding lute, book, and prayer beads. Goddess of literature, learning, and music, she's the old Vedic river goddess equated with Vac, speech. I've seen her placed atop printing presses,

books, school desks, and sitars on her feast day.

In Kolkata a child is given chalk and slate, bestowed with prayers, and initiated into literacy. On Tagore's birthday, books of his poetry are exchanged. At the Kolkata Book Fair, authors and publishers meet the public in temple-like kiosks tacked together from canvas and bamboo, laced with flowers and colored lights. When not broadcasting Tagore's songs, loudspeakers summon thousands to hear their favorite writer in a simple tent. ATM machines are there to nourish buying sprees. Bengalis have always understood that one way to leave home without a purchasing a ticket is to book a passage on a fine novel, or settle into the classics, the social realists, or the epic poets. This is why Bengalis are so notoriously open. They've traveled elsewhere through words, stanzas, finely-tuned imaginations. Close-minded "culture" is

for those who have forgotten how to read.

in the book store

a man sewing a binding

to Vedic chants.

∴

From a bend of peeling mansions, a battered trolley gives a sudden rumble. Renée and I grab each other like kids, unbelieving, as the wobbling headlight shines into our eyes. The tram jolts and sputters below a maze of wires, dreamlike, close enough to touch, a child's cardboard cutout riding a crayoned track. We're momentarily part of the bygone as it canters before us, then squeals and jerks out of sight, tilting around a slow, leafy corner into the hazy sun: a di Chirco painting.

We head for the India Coffee House, navigating a teeming street market en route. Renée notices the word D I V I N E floating above the crowd on a nearly-invisible wire. Just below, Kali gives a fierce smile. Her tongue is out, fluorescent red, there's a marigold-draped hatchet in one hand, incense curling between her toes. I feel a persistent tap on my leg and look down to see a beggar sprawled stick-like on the brick paving. Under his rag-draped body, each brick is stamped with the word: MAYA. Up the alley as far as the eye can see: MAYA MAYA MAYA MAYA.

Behind ragged awnings, type fonts clatter. Printing presses clank under dripping balconies ornate with metal grilles wrapped like bars of music around yellow façades stained tobacco brown. Gamblers hunker in a chalked circle, slap finger-soiled aces to the ground. Odors of mercurochrome waft from a chemist's door. A cat leaps out, mouse in teeth, nearly topples a tray of writing paper next to a scribe wrapped in a loincloth. He's cross-legged on the sidewalk before a portable Olivetti. Tacked to the wall behind him is a sampling of letters (bereavement, condolence, marriage, appeal, court proceedings) that he'll type and post for a small sum. The tangled streets buzz with shoppers. Dentures clacking, mouths betel stained, canes tapping, flesh shaking — they fumble through clothes, face powders, hair oils, rat traps, deadbolts, doorknobs, and polychrome images of the gods. My eyes are jet-lagged, nostrils on overload. My nervous system wants to log off, but the streets stubbornly insist on their smells: salted fish, rose petals, ayurvedic soap, dung patties stacked like poker chips, vats of boiling milk, moth-balled silks, bubbling tar, men's Legal Wear Sterilized Briefs. The alleys lift and fray, their edges like burnt celluloid. Everything's askew, as if one had taken too many anti-malaria pills. The ultimate psychedelic window is reality itself, a high comedy of walking paragraphs clumsily typeset on samsara's page.

∴

I am made weary to jot this all down. I need centuries, galaxies of time to gather the inanity, the chance-rarity, the phosphor silence between the high moments of surprise. Kolkata burns like a wreath around my skull. Belches, sags, crackles up through the nose. It's all stumble and wonder, mad talk of the living, rice water in banged aluminum pots, bony hips of the dying, red beards with skull caps, stick figures in ironed suits, a man with a floor-mop face, a walking tent whose eyelashes flutter like lost sparrows behind its cloth screen. Kolkata is the radical underground, the rickshaw pullers mobilizing their ultimate push, a poet liberating sound from flesh, a disgruntled housewife pawning her bangles, a sadhu reciting a litany, working on his ego, bowing to his own photograph. In the evening heat, the soul wears henna, the spigot begs repeatedly. In rush-hour traffic a fire-eater shits flames, a pair of perfect buttocks j-walks the tram tracks, one cheek keeping time to the other. Kolkata: unstructured bewitchment, a knot of chaos. The tighter it is tied the more it undoes the mind.

through the leaves

a broken sky, in the throat

a knife's edge.

A bus is coming, elbows out the windows, riders hanging from its tail. At the bus stop wait the burka-clad (clutching purses and musically-ringing cell phones), the business men (slim leather briefcase embossed with gold initials), a hotel worker (straight-backed in a starched-gray uniform), and a gaggle of school kids. Above them is a half-torn poster of a sweat-dripping Bollywood actor saving a cleavage-heavy damsel from a panting locomotive. Now comes a magnetic set of breasts bouncing under a shirt that says DOUBLE FEATURE. Between the anointed and the smoke-ragged, a monkey bites his tongue, a cauterized arm offers a string of jasmine, a hungry coolie wheezes under a well-endowed manikin. Over lap dancers and diamond cutters, milk churners and memory swallowers, a crystal arc sprays from a balcony. A boy taking a piss.

Amid terrors of gloom

one leans to the muse (Verlaine)

∴

Paralysis overtakes the senses. I know I've left home because I've been tossed into the stream. I am in Kolkata without a wink or a lip, and someone's reading me like an old book. It's the blind man with fingers of Braille. It's the low-cut siren undoing my jeans. It's the howl of the Beast, the ancient chase between shadow and symbol. Anarchy! A tameless river carving its own course—as opposed to the tamed river of democracy whose truth has limited options and cataclysmic expansionism is the order of the day. Who in Kolkata would trust a moneyed war-monger puppeted by hawks who regard themselves above the law?

on the veranda

a silver-glazed cup

is smashed to pieces (Basho)

What would Basho do in today's world? His plight would be that of a poet wanting to sleep in the grass and befriend the seasons, yet having to face the population explosion, heavy industry, electronic wrath, the lies of policy makers not only disconnected from nature, but torn from their own souls. Wandering through chilly winds, facing the autumn stars, seeking a balance between the strife of his times and his inner struggles, the wind surely pierced Basho's cloak; but it was not the wind of falling skyscrapers, suicide bombers, nor the ten-million-degree wind over Hiroshima flattening an entire city. Basho was blessed with smaller times. The cook fire was low, sweet smelling. Trees, when talked to, replied. Amid the flies and pasania blossoms he was free to wander, to report on the poignancy and comedy of human life; sans passport, credit cards, government grants, health insurance, PhD, tenure, social security, or burial plan. Pedestrian, humble, earthbound, he was a fragile creature within the greater organism. A man filled with memory, personal struggles, curiosity, delight in the small. From the stillness within his journey he could open, expand, seek friendships, become a teacher. He could empty his head, regroup his thoughts, seek source and renewal in places unfamiliar. Rough seas, dark canyons, lichened crags, foggy heather, even the wood-slat mercantile alleyways of Edo — all were humanly manageable.

Ay, but it is no longer Basho's time. The lamp is lit with coal factories and dams. My shoes run on jet fuel. I cannot pretend or force today to be then. I am on Sarat Bose and Rashbehari, walking in sandals that aren't Basho's except by metaphor. Kolkata is hardly manageable, yet it is this state of unmanageability that drives me to my innermost center. What do I discover in that whorl? That I am a poet! Steered by the whims of the rivers beneath me, rudderless like a reed-woven raft on the rapids. And it is this raft — the raft of poetry — that makes the rocks, rapids, and bogs navigable. On it, I catch a peek of clear sky through the muck.

300,000 years into it

and human folly

still with us.

The earth is quaking, seas are burning, forests are withering, and wars are sending mass migrations across the deserts. No Moses for this exodus; the promised land has been torched. All I want, as things rapidly speed up and collapse, is to grow into the soil and spread my roots through its fecundity. As wildfires roar from no-longer-dormant volcanoes, I'll go the road like Basho — seek the dream that calls my name, find the paradise that I've been ejected from. I'll meet new people, create dialogue, have an exchange, refresh my thinking beyond the walls of the ever-bullying empire that has imprisoned its rulers as well as their subjects. To leave home is a big step nowadays. Too many Americans are frightfully tethered, xenophobic, afraid to go beyond the wall. There is hope, though. Amitav Ghosh, a Bengali writer living part time in Brooklyn, says: "it won't be long before most Americans begin to dream of

escape from the imprisonment of absolute power."

∴

old pond

a frog leaps in

splash.

What is the meaning of Basho's poem? Last summer I saw the frog jump out, not into the pond, through a rusty bicycle rim. Beyond leap, splash, ripple, murk, and all non-amphibian interpretations, the frog seems to imply: "Move, don't just sit there and think." Kerplunk, get dirty! Travel to unravel. No guarantee you'll resurface. But if you do, you'll come out a different creature. Basho's need to "leap" had its roots in previous generations of Chinese and Japanese poets who ventured largely for purposes of literary discipline. What made Basho different was his elevated curiosity for a world beyond his usual surroundings — a spiritual impulse to go toward the unknown. A stanza from Rilke echoes this impulse:

Sometimes a man stands up during supper

and walks outdoors, and keeps on walking

because of a church that stands somewhere in the East.

If "a church that stands somewhere in the East" calls, or if it happens to be in the Yoruba barrios of Havana, or in the radical Chiapas backcountry, beware. Your quest may be disallowed. Governments are pulling the buckle tighter. They are watching us, attempting to monitor our imaginations, our actions, our quests. Perhaps it's best to remain in your own watershed, dip the bucket deep, drink from the source, raise your children in clean air, quarry river stones, plant healthy crops, glean the rose hips. If you choose to leave, take caution. Whether you head to Memphis or Mumbai, you're fated to meet a majority hooked on "bigger, better, faster." The "upgrade society." Fortunately, it takes only the slightest effort to seek the exception, the maverick, the alternative, to make the journey invigorating (when there are no alternatives, it becomes necessary to create them).

You won't meet the rebel by joining eco-tourist, new-age, shamanic, Condé Nast, or soldiers-for-jesus tours (why would a guy capable of miracles need soldiers?); nor with pre-packaged trips for students primarily interested in getting all A's for the money they've paid; nor with scams that promise "something different" by getting you into "remote areas" that have been over-invaded ever since mass tourism caught on in the 70s. "Hill trek to lost tribes using Stone Age tools" (how about tools of the 1950s?). "See ring-necked beauties of yesteryear as we raft you through misting waterfalls into untamed jungle." But it's all bogus. Bought-and-sold clones of a naked-and-painted past. People who go about in jeans and t-shirts and

change into tribal attire just before you arrive.

There's nothing like traveling on your own. If you must find another, go with a rogue, lock-picker, j-walker, revolutionary, advanced lingerer, clairvoyant, or with souls yet to be born, a ragtag trio of Nadistas, a comrade who loves surprise and disdains having things under control. If a poet, find another poet to look up when you get to your destination; a person who walks on the edge and isn't afraid of heights; an anti-capitalist who knows how to enjoy life; a soul sister or bold brother who has stood up against the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and the plethora of wars that have plagued our existence non-stop since birth; which leads me to the inevitable question posed by the war weary: "What to do?"

Every time we travel, the issue arises. No consoling answer, but it's helpful to remember that those running the war machine have arms that reach only so far. Their slaps often extend only into mid air, though people think they've actually been hit, knocked down, and they don't feel like getting up again; which is when the oppressors win. "Remain alert so as not to get run down," advised poet Lew Welch:

You only have to hop a few feet to one side

and the whole huge machinery rolls by,

not seeing you at all.

We halt in a blackened doorway where a child offers a recycled friendship bracelet. A mop slops the stairs in the hands of a tired Cinderella. Here, where Park Avenue intersects Mirza Ghalib, a swelling microcosm boils up from under my feet:

a rainbow rests

on the curb, the broken vow

becomes a doorstep infant.

∴

India Coffee House. The place has seen better days, but it's a must-see institution where revolutions were planned and famous artists—Satyajit Ray among them—fleshed out scenes for films, books, and stage plays. The massive high-ceilinged room has been going non-stop since the 40s, and still echoes with the chatter of students and intellectuals gathered around metal tables set with coffee and snacks. Tagore's portrait looks over them all, gracing the otherwise empty walls. The waiters wear soup-stained jackets and faux-colonial caps. They don't smile, they don't frown. They make their rounds, efficient and unrushed, under trays of steaming coffee and English sandwiches with the crusts cut off. Ceiling fans twirl, talk simmers into whispers, then rises suddenly — like a bucket of clattering nails.

Adda is the great Kolkata tradition of spirited talk, animated dialogue, hearty conversation, enlivened gossip. It reminds us of Havana coffee parlors, Hanoi espresso dives, the clink of spoons on glasses in Vera Cruz. Ascending the worn cement stairs past a hodgepodge of political posters and theater bills gummed to the walls, we're hit by the wired, bombastic buzz of discourse. This isn't the soft-spoken "let's do lunch" prattle carried on over tablecloths and heavy silverware in American cities; it's raised-howl, opinionated, sometimes funny, often combative talk rip-roaring from several bare-metal tables at once — an operatic repartee full of cerebral anecdotes; literary, political.

A good adda is refreshing and rewarding . . .

a safety valve that protects people from

the hard realities of Calcutta life.

(Krishna Dutta)

We wonder why the India Coffee House hasn't been spruced up over the decades. Maybe the cost of paint and labor would double the price of coffee, making it too expensive for the student clientele. Coffees go for 10-12 rupees, samosas for two rupees, bread and butter is four, meat curry 23 a plate (exchange rate = 45 rupees per dollar). Nope, spiffy it up and you bring in the moneyed and exclude the students. Never! It would go against Kolkata's socialist leanings. There's something compelling about a city with an aversion to cosmetic change; with emphasis instead on the cerebral, artistic, poetic; on the austere, rough-edged beauty the Japanese call wabi. A friend in the States told us before we left: "I suspect the unrefined tumbledown quality, the anarchy and mayhem of Calcutta, would be a bit too real for most American poets." But why should it be? It's the perfect threshold, the ideal metaphor for the absolute chaos one experiences during any true creative act. How about Lorca in New York?

City of musk and sorrow with your cinnamon towers . . .

your blood shaken within dark eclipse,

your garnet violence deaf and dumb in the penumbra . . .

who could see you and not remember?

∴

9 October, Kolkata

A general strike's been called — not unusual for Kolkata. After all, this is the city where 250,000 took to the streets to protest India's nuclear tests in the late 90s. Ranjan says any political decision made in Delhi not of the dominant Communist Party's liking will be protested locally. The strikes are effective, sometimes violent. They can shut the whole city of 15 million down overnight, cutting off water, electricity, and transportation in a wink. This morning my water stopped mid-shower; fortunately there was enough water in the bucket for a rinse. Without traffic the sky is clear; without many pedestrians the streets are, too. We enjoy another South Indian breakfast at Rao's. This time we sample upma, a toasted-semolina porridge seasoned with cumin, ginger, green chilies, chopped onion, and mustard seed (plus dwarf peas and a dash of pureed, roasted eggplant). We wash it down with fresh-squeezed lime juice in sparkling water, then return to Vasudha and Ranjan's to write in journals, and walk.

∴

The neighborhood is full of quaint, neo-classical apartments with curved façades, art-deco ironwork, baroque balconies. It's leafy, friendly, full of life. On a three-block stroll we discover backdoor gardens filled with flowers and herbs, a woman bowing before a corner shrine, a tailor following a tissue-paper pattern with a giant scissors, a doorway marked with vermilion-paste swastikas over a table of precisely-folded shirts. A prim brick apartment is signed with SHAKESPEARE SOCIETY; a sari shop warns: NO ENTRY WITHOUT BUSINESS. On a shady corner is an aquarium on a concrete pedestal, fish playing inside (in an American city street gangs would poison the fish and smash the glass). A man walks up and says: "Oh what a fine gentleman you are," as he boards one of those minimalist rickshaws found only in Kolkata: hand pulled, wood wheeled, a single sun-cracked vinyl seat under a fragile canvas awning. We take a break at "Sree Alterations Shop."

the tailor's flatiron —

a boat on a sea

of coals.

Several streets are devoted to a vegetable market. Men in lungis, women in diaphanous wraps sit on the ground before arrays of crushed spices, bitter gourds, purple mangosteens, radishes, baby potatoes, pickled lime, dal, garbanzos, jackfruit, quince, banana leaves, coconuts. Everything is spread neatly on squares of colored cloth: kindling wood, charcoal, grinding stones, cheese, milk, sweets, mustard oil, ghee; saffron, sandalwood, antimony, third-eye make up. Roots and bark are good for spontaneous bewitchment, mental cures, erections. Ground-up carapaces induce erotic dreams. You needn't spend much for a cure here; they'll give you free samples if you are dubious. And it's fun to engage, chat, and be

on your way after a simple bow with folded palms.

We buy roasted peanuts wrapped in cones made from the daily news. Hawkers converge and display their upside-down umbrellas filled with Krishna keychains, Kali magnets, bundles of votive flowers. They are disappointed but good natured when we wave them off. Other vendors hawk brass lingams, soapstone yonis, and suspicious jars of Thunderbolt Face Whitener whose label guarantees the cream will "fascinate the face for work or college, removing first apparitions of old age" (I'm due for a jar!). One man proudly balances the final matchbox on his three-foot pyramid of Jungle Fever Safety Lights, each box printed with a smiling gorilla clutching a woman in a shredded mini-skirt.

Why do we come here?

To find in reality what we usually see only in dreams.

To regain perspective within the Strange —

∴

We meet a young French volunteer who works at Nirmal Hriday, "Place of Pure Heart," Mother Teresa's home for the dying, and take a walk over there with her. We noticed a group of Missionaries of Charity in Kolkata's airport; some Indian, some foreign, in simple blue-bordered white saris. Now we see them at Mother Teresa's, side by side with lay volunteers, tending men in one room, women in another, allowing death take to its course; no heavy pharmaceuticals in the way. The plastic-sheeted death beds are occupied by those about to give up their bodies and leave the human community. Some lie flat in semi-sleep; some are curled like spiders immobile in webs; others twist and turn, miserable in their prolonged state, leaking pools of urine which are immediately mopped by the staff. A patient growls and claws at hallucinatory visitors; another sits upright, Renée talking to her as

if she were a neighbor or relative, realizing, yes, she is both.

What code of factors determines which individuals are to be plucked from the destitute that fill Kolkata's streets and brought to Nirmal Hriday? We really don't get an answer (who has time for us amid the dying?), but I later read that when a hospital can't find space for the dying, they are taken to Nirmal Hriday where they can at least have a bed to themselves, personal attention, and some kind of rite of passage. It'd be interesting to learn exactly what drives foreigners to work at Mother Teresa's. If you're tired of peace walks and the passive signing of petitions while you watch the world being destroyed and remade for the rich, or if you want to take a sword to the ego and practice non attachment, you may be ready for Nirmal Hriday; to dirty the hands changing diapers, emptying bedpans, cleaning sores,

washing the blue rubber mats of the dying.

Mutual aid is one way to render impotent the world's rampant military machinery. No doubt humanity is ready for extinction, unless it can be steered away from its violent habits. We've got to be vigilant against tight-jawed men who find virtue in violence and create boundary after boundary—and guns, bulwarks, and barracks to go with them. I recall a tagged wall in Chiapas that would carry its message very well in Kolkata:

Guerra no, lucha sí War no, struggle yes

Apoyo Mutuo! Mutual aid!

Accion Directa— Direct action —

We don't want to become voyeurs, so don't linger at Mother Teresa's. Next door is the Kalighat Temple, circled by priests and beggars, and merchants vending mass-produced images of Kali, as well as the usual over-sweet incense, ritual brassware, hibiscus flowers, and devotional powders. The priests encourage us towards what part of the temple is okay for non Hindus — for a small fee. We aren't interested. The bloody sacrifice of goats is still performed inside, though yesterday's Telegraph said the practice has been banned in many temples of West Bengal, most recently up north in Siliguri, where the goat sellers are marching in protest. "The abandonment of the ritual is a serious threat to our business."

the dying woman —

they've moved her to the bed

closest to the door.

∴

10 October, Kolkata

A thwarted venture to Shantiniketan village to see Rabindranath Tagore's paintings, manuscripts, and his father's ashram (in 1901 he converted it into an experimental, open-air school). After a three-hour train ride upriver from Kolkata, we arrive to find Tagore University, museum, and library closed for the holidays. Worse, the Bengali friend of a friend who's acting as our guide is rushed, of ill humor, and unable to secure the promised bicycles we were to explore the countryside on (likely he doesn't want it to happen). The experience is atypical of the usual camaraderie one enjoys with Calcuttans. We tire of walking and hire an auto rickshaw to visit a crafts shop; afterwards stop to peer through a fence at the Tagore house where an armed guard scoots us on. At a roadside dhaba we eat a rather bland egg curry with rice, then nap outdoors on charpoys in the shade of the mud-walled kitchen. Bollywood music crackles from the cook's transistor radio. A chocolate-skinned boy wearing a pink-checkered lungi brings water from the well,

hopping nimbly on one leg, his deformed one dangling.

Our guide wakes, we pay for the meal, and off we go trying to keep up with him. "I know a Dutch painter married to a tribal woman, let's go visit him." These Dutch painters are always married to tribal women. I've seen their ghosts in Bali, Thailand, Santa Fe, and now India. "I'd rather visit a farmer," I retort. We end up back on Shantiniketan's main drag amid dust and Indian tourists. There's a 6 pm a/c express train back to Kolkata, but our guide — who seems antsy to return to his European girlfriend — insists we jump the 3 pm local. Reluctantly, we agree.

It's a slow, crowded grind. The coach is bright with late-afternoon sun. The glow illuminates the dark skin and glass bangles of village women, the taught, curious faces of their farmer husbands, the wispy silhouettes of their sparkling-eyed daughters, and a jumble of brass cook pots, farm tools, and cackling hens. It's the only "light" moment of the venture — ironically having to do with the quality of light being cast by the reddened sun lowering over rice fields hazed with moisture and dust. Some writers would say "Monet-like light," leaning on the obvious European reference. But this is the light of India, strictly of this place. I mention it to our guide, and he gives his only smile of the day: "This light is particular to our continent. We call it godhuli—'time when cows come home'. It is the hue made by kicked-up dust, the kind of golden haze one should first see his bride by."

a steady gaze

from the farmer's daughter

sharpening her knife.

∴

Late afternoon. We pull into a station called Prantik, "the end" (certainly feels like it!). Here we learn that we must change to an even slower train. The massive crowd of transferring passengers literally sweeps us off our feet, up, over, down the bridge to the other side of the platform. I'm literally carried by the press of the mob, feet dangling above the walkway. The new train is impossibly jammed. We are wedged into a cage-like bogy with barred windows, ceiling fans rotating, hawkers hawking, minstrels singing off key, rattling their alms bowls. Countless staring farmers surround us. For the remaining two hours to Howrah Station we put up with the overtaking of what little room we have on our hard wooden benches by the expertise of those familiar with the art of finding a few square inches of seat — right between our legs. At one stop the urchins appear: little girls in canary saris wearing paper wings, cheeks pasted with sequins and red dots. They carry toy bows and arrows and meander through the crowd reciting verses from the Ramayana — then demand money. Next comes a blind kid being led by his sisters, or maybe he's just faking, eyes closed. He does his job well, though, and ends with a cup full of rupees, and we with a well-fingered card:

DEAR SIR / MADEM, BEARER OF THIS APPEAL IS BLIND & GOTS FITS

COMPLAINT. HIS TWO SISTERS ARE DUMP & LAMB WITH NO INCOM

BUT TO SEEK YOUR HELP FOR THEIR LIVELY HOOD ON EARTH.

MAY THE GODS BLESS YOU WITH FOOD, HLEATH & WELTH.

The finale is Howrah itself, the largest train station in the world. "Never ride third class," I'd warned Renée before India. Previous experience proved that taking a train with no reserved seats into a big city station meant bulldozing out of the bogy, screaming like a 49ers' quarterback, all arms and elbows, as oncoming passengers simultaneously stampeded aboard crushing anyone in their way: cripple, orphan, little Mother Teresas, the old baba on his crutch. I suppose one should have compassion for these charging maniacs. They're usually the lowest of low: tired, hungry workers slaving all day for next-to-nothing pay; all they want is to return to their

dirt-floor abodes sitting, not standing.

On our own we would have lingered in Shantiniketan, taken the express, and avoided what we were about to face. As the train slows into Howrah, the waiting masses begin their charge, running alongside the coach, grabbing window bars and door rails before it comes to a stop. I fear for Renée, but she doesn't need my protection. She's amazingly up to the challenge, even enjoying herself. She immediately puts into action (or non-action) her Aikido practice, lowering her posture, narrowing her stance, bringing arms in around face, becoming small and agile. And it works! She's easily out of the coach before her husband, who's busy reacting, resisting, complaining — wishing none of it was happening—yelling and charging like a bull, only to be stopped

by the lead weight of several other bulls.

∴

11 October, Kolkata

Tonight we take the double-tier sleeper train down the coast to the temple city of Puri. I'm leery of returning to Howrah. Renée humors my apprehension. "All of it, even when you're imagining it, even when you're in the belly of it, is only temporary." I suggest we take a plane. No, she laughs. We're going with the plan. "How will we find the right platform in that mad crowd, or know which train is ours?" No response. Howrah it shall be.

Last night we visited the idiosyncratic Fairlawn Hotel on Sudder Street, an old standard (the building's been there since 1783) still run by the heirs of the original pre-independence British managers. The lobby reeked of fresh green paint, the staff busy re-tacking the walls with framed memorabilia, ticking clocks, and some awful ceramic knickknacks. Writers like Eric Newby and Dominique Lapierre have stayed here, as well as actors like Shashi Kapoor and Patick Swayze, presidents like Clinton, and a famous 1950s wrestler named "King Kong" who broke every chair he sat on. The leafy garden was a relief from Kolkata's heat, its big trees strung with festive lights, tables set with cold Kingfisher lagers, chairs filled with an interesting mix of travelers, business people, eclectic urbanites, and a few Bengali socialites planted amid them checking out the action.

A French lad appeared at our table, pulling up a chair next to the Mother Teresa volunteer who was part of our randomly-assembled group. They began talking in French but she quickly switched to English, partly out of politeness, partly because the conversation was not of her liking. He was a backpacker. Dark-ringed eyes, badly-cut hair, cold sores leaking at his mouth corners. And plenty to whine about: "There is nothing amazing about India. Two weeks I am here and I find nothing incredible. So now I leave."

He glanced around for a response. I threw in my two cents: "amazement happens when you least expect." "Like what?" he scoffed. I told the story of our first morning in Kolkata. The child-like trolley appearing from nowhere, vanishing in a flash, cantering between peeling mansions with their bars-of-music wrought iron. I tried to evoke the sense of wonder it generated: "Like a dream, except it was real. You could climb aboard, disappear." No reaction. I described walking the alley where Kali had her tongue out over a beggar lying on a sidewalk paved with the word MAYA. The French boy was unmoved. "It is better I leave."

I thought of Mallarmé: "A toss of the dice will never abolish chance," but kept the words to myself. "Where do you want to go?" I asked. "Andaman Islands, Thailand, maybe the Similans. I need to move." I suggested he slow down, give India a chance, take some unexpected turns. This upset him. "I'm 23 years old. I've done the contemplative thing. I want action." He took a swig from someone's beer and got up. Jesus, I thought, only 23 and he's done with the introspective thing? Unhappy, looking for an escape, he grabbed his tower of a backpack and was off in a flurry. George Orwell once wrote: "At age fifty every man wears the face he deserves." This kid was already wearing that face. As he went out the gates I noticed a big box of Cornflakes tied to his pack (restaurants catering to Westerners list them on their menus as: "Corn Fakes").

evening heat

a cool breeze from

the passing waitress.

∴

We repack for tonight's train ride and the Orissa coast. Boots and jackets we brought for the Himalayas we'll leave behind, taking only light cottons and sandals. Vasudha fixes us a fine Bengali meal: spicy shrimp in mustard paste, tomato curry, brown basmati rice, alu, and okra — followed by masala chai. We — try calling Kolkata poet, P. Lal, but his wife informs us that he's terribly sick with bronchitis after their holidays. "It was the freezing air-conditioning on the Puri sleeper train that made him ill." We wish him quick recovery and decide to pack our Himalayan scarves

and wool hats for the same train ride.

There's an immediate camaraderie here with Ranjan, Vasudha, Mishti and all their visiting friends: artists, writers, songsters, movie makers. Seems if you work and think and jostle along the right path, it moves you towards what you need: the people, the places, the encouragement; perhaps even the rewards (though maybe not the kind you were imagining!). The requirements: be yourself, tune your ears, give room for whatever rises from the ferment to reveal its truth.

Our business as poets is not to be successful,

but to be honest, see past the muck, go beyond it

— in our lives, our visions, our work.

(David Meltzer)

So many clever poets out there tolerating each other, while elbowing to the top of the pack, nestling up to those who control the money and power. Wiser to become smaller as you age, less visible, less connected with literary establishments that juggle people around, setting up competitive situations that dampen creativity. With honest comrades along a narrow path, you can be who you are, and garner a success more worthy than what the establishment has planned for you. Everything that poetry often tries to be — bigger, better, louder — goes against its nature. I'll always bow to the words of Vietnamese writer, Le Thi Diem Thuy: "People are often larger than their situation. Make yourself small in order to absorb it all. Pull everything into a kind of cool perception. Pull the people who are in the backdrop forward." Become the face you do not know. The precise cinema of the world won't spill off its reel into the body unless nerve receptors are relaxed, ready to perk. Keep cool and the heat of your encounters will rise into clear flame. Start with the emotion, write from what unfolds. Any order of arriving imagery within the ungainly randomness that surrounds is the right order from which to begin.

It's good to be sharing Ranjan and Vasudha's flat with co-creators in whom we can trust. No hierarchy, no this side or that. We can divulge the specifics of our individual selves; be teasing, provocative, vulnerable, and totally "in" because we're outside the loop. Best of all, we can hang out after everybody leaves, knowing the party's never over. Kerouac, in an early journal (he was in his twenties) celebrates "solace in the raw world. In Human people, loving, trusting people … a classless society undivided by pomps and worldly vanities and envies — a dream not of perfection in the world but of simple desire for happiness and fruition, a sincere struggle."

haiku competition —

all those 5-7-5 poets

moving their fingers.

∴

We take another walk in our neighborhood. Effigies of Kali in makeshift shrines. Sewing machines working overtime. Carpenters flying about like spider monkeys on bamboo scaffolding. Each block tries to outdo the other with a painted deity, tinseled temple, and a knee-jiggling band of musicos drumming and tooting while frenzied dancers lose consciousness amid popping fireworks. One shrine's canvas is spray-painted bronze and scarlet, its entrance spanned by a split-bamboo arch braided with marigolds. It's like feast days in New Mexico: the dusty plaza of Jemez, deities arranged on a plastic-flowered altar inside an open-air shrine plaited with juniper boughs. People kneeling on the ground, eating from paper plates (in India it would be banana leaves). Chile, posole, boiled squash, bread pudding, coffee. The caciques firing rifles as half-humans/half-animals prance into the plaza, their anthropomorphic presence not unlike Ganesha with elephant head and human body, or Hanuman with Superman torso and monkey head. A world not quite what you see, that's the world I want to live in.

Resting on the earth

who needs satori or faith?

Embrace what holds you!

(Edith Shiffert)

∴

12 October, Puri

Hazy, humid, fierce breakers, bad undertow. No one trusts the skinny lifeguards walking the beach or playing cards with barely-inflated inner tubes around their waists. Indian families bathe fully clothed, the women revealing just about as much in their wet, skin-pressed saris as they would in the raw. More is less. They look very erotic this way.

a smile from the dark one

as she struggles from the surf

tangled in wet silk.

We lodge in a two-story manor that formerly belonged to the raja of Serampore: $10 for two. Inside the thick walls it's naturally cool. Our room is airy, with ample bed, huge bathroom, plenty of hot water — though it's hardly needed. Bougainvilleas lace the balcony, the Bay of Bengal sparkling between their magenta flowers. We shower, order prawns, cucumber salad, two beers, and settle in. The staff is friendly, the cook — as we are to learn — is a master with fresh seafood. The desk clerk is the Orissan version of Screaming Jay Hawkins in Mystery Train. He doesn't have a gruff voice, but whispers sweetly — perpetually bent over a massive hotel register, doing his duty, pencil in hand, a responsible but mischievous look in his eye.

∴

Before bed we linger in Puri's sultry night, share a tall bottle of beer, review notes we've scribbled on Kolkata's sidewalks, trams, and tea stalls. Kolkata isn't on the map for most Americans. They can't imagine how much JUICE it has. Its people, conversations, streets, architecture, and nonstop stream-of-consciousness imagery is so entrenched in my body that it continues to boil up and out through

my pen like a dervish under the desk lamp.

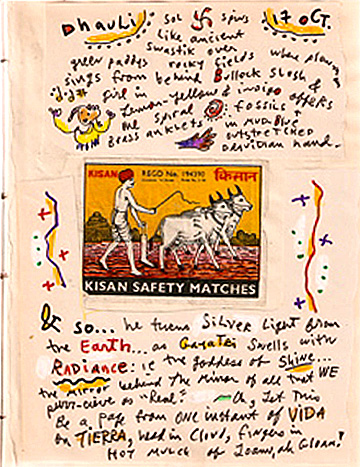

I want to return to Howrah Station . . .

Getting there from downtown Kolkata was a broken-shock, bald-tire, sagging-spring acid trip. I think the mad cabbie thought the faster he drove, the higher his tip would be. What a thundering daredevil—squeezing through impossible spaces with persistent horn honk, rapid acceleration (my neck still hurts) and staccato braking. But he got us there, plenty of time to spare. From central Kolkata you have to cross the Hooghly, inching your way over its dark waters on the 27,000-ton Howrah Bridge. By foot, rickshaw, bus, or taxi you fight your way through the clamor, sucking in exhaust and spittle-hack, ears pounding with rattling trestle bars, clobbering hoof-kick, and wallah-shout over slow-turning axels of carts piled with rebar and rice. If you hail an antique cab, likely its meter will be broken, its windows down, and bumper to bumper you will creep, inhaling toxins behind a hundred other taxis, revving and shoving through acetylene flare of welders strapped to the sad fretwork of cables and mesh. And always there's the rag-of-a-doll child, scarcely out of the womb, precariously close to the traffic, outstretched in the begging mother's arms. Or a spindly guy, half alive, pedaling a makeshift contraption, his head like a burnt match,

eye-level with rusty bumpers.

Below the bridge, guttering lights of top-heavy barges splutter by. Above, the sky is a hazy all-night khaki. Vague movie-set shapes brighten and disappear in factory flare. Billboards light up with giant legs, vodka bottles, pearl chokers, silk underwear, Japanese televisions, perfumed eyelashes, and sexy laptops — but not plow handles, yokes, scythes, or seed. Above a brittle nest of destitute campers in the street, a pharmaceutical company's billboard depicts a baby sleeping inside a big blue pill:

WE HELP YOU LIVE LONGER.

∴

Kolkata gives unbelievable dimension to joy and despair. In other cities, these adjectives are often a veneer. In Kolkata they swell from a dark, paroxysmal pool like a glowing anemone; or they retreat into an eclipse of cloying purple ferment. One has a sensation of morphine in the limbs, a rubbery fatigue (like Artaud describes) not of muscular tension, but "a fatigue of cosmic Creation, a sensation that the body is being dragged on and on." Kolkata is picture show upon picture show, a kaleidoscope of disembodied imagery. One feels incredible fragility coupled with staunch determination. I'm going to make it to the next block. I'm not going to wince at dire odds.

I am going forward with utmost hope.

"Compassionate" is a better word for Kolkata than adjectives of spectral despair most westerners bequeath upon this city. Compassion for millions of refugees from Bangladesh, Kashmir, Bihar — and for the sagging infrastructure that can hardly bear their weight. Between 1947 and 1951 alone, nearly two million uprooted migrants entered West Bengal. They were accommodated, even if sewn-together tarps were the only way. Resilience, resourcefulness, and cooperation are taken beyond their conceivable limits in Kolkata. By comparison, America (who likes to brag of its wealth and superiority) couldn't even deal with an emergency like Katrina. A New Orleans neighboring city actually refused hungry, homeless refugees from the floodwaters;

they were turned back with guns.

Kolkata provokes the most unimaginable emotions. Sometimes it's a startling wonderment, an unfolding lotus blooming from turbid muck. Other times it's the collapse of everything familiar into the teeth of a grinding gear. Maybe you had no belief in the the Divine Goddess (or in her Kali aspect), but if you give yourself over to Kolkata, the breakdowns and alembic highs, you soon come away knowing she's there. From her were born the gods, and yourself with all your concepts of god. Like Alice, you grow smaller, able to fit through any door.

You discover humility, and in humility, courage.

Kolkata. Elegant, vitreous, immune, defenseless. You want to get where you are going but where you are going is where you are. Titillations and sidetracks rupture all plans — because they are all absorbing. I sometimes hear Baudelaire, or Piaf, faceless in the crowd; watch Kali dance from the strings of Leadbelly. I hear the Marvelettes sing from an open-mouthed gargoyle; feel the ghost of Patsy Cline. I fall to Pieces. I melt like the stripes of a tiger. I bed down inside the eternal conversation — with the electrician, the poet, the floor scrubber. Or find relief in the sheets, tangled up with Parvati, searching for her lost earring. I hear puja-clang, tabla patter, a wheezing box organ, and discover Gandhi — not in the Oxford Bookstore — but as a nameless genie in exhaust haze, his glasses fogged in the essential mystery, the guesswork of anticipation. I hear Ginsberg, too:

An ogre goes with every rose,

a bee sting guards the honey . . .

But I had been talking about Howrah Station . . .

its church-like chamber, its brown echoing halls. The smell of coughdrops, paan, lime, and leather. The clinggg of bangles, the monologues of the lonely. Myrrh on the earlobes, antimony at the eye corners. Sweat, acrid and sweet, from necklines and secret folds. Vishnu's miniature foot dangling above the cleavage of the musk-nippled bride to be. A handbook on right attitude might help you through Howrah. Or a logistics manual to figure the math on how to perfectly sidestep the overloaded porters, the crazed rush of commuters, a sudden pothole, a slippery streak of spilled ghee, the sleepers on the floor inside their temporary suitcase walls. A little lunacy might help, too. Inside Howrah are more people than you will likely see at one time in one place in your entire life. Amid the ticket holders, some people seem camped forever on the floor — no ticket, no home, no goal. The same sleepers you'll see on the ghats of Varanasi — only their destination is death; they have come to camp in Shiva's city next to the Ganges. They have come for moksha, liberation;

the final crossing of the river to the Far Shore.

The amazing thing about Howrah is that it works. What seems like pure anarchy holds a certain intuitive order. People are helpful. We found our track with ease, and to our amazement, in a station handling millions daily, our names were posted on the dispatch board along with train, coach, and berth numbers;

everything booked online 12,000 miles away.

∴

The train to Puri . . .

Once aboard, people eight to eighty climb into assigned berths, undo bedding from paper wraps, and make up their bunks. A slumber party on wheels.

all night

bangles clinking

under the newlyweds' blanket.

We meet an Indian couple from Orissa, Anita and Sanmath, who lived and worked ten years in the States, sold their home, and are returning to India. By the time we awake to Orissa's shimmering rice fields, we've been invited to Anita's mother's home in the old part of Puri. They want to share prasad with us — sacred food prepared in the famous Jagannath Temple and blessed by the deities. We thank them, make a plan, and go back to watching the remaining two hours of scenery pass by: mango groves, sparkling paddies, snowy herons riding water buffalos, kids splashing in ponds, clay roads glinting like flint, oxcarts filled with pick-and-bucket village women in parrot-colored saris. Where to, where from? And how can time be measured with clock hands amid such beauty, such sadness, the whole show

lopsidedly creaking along on wobbling wheels?

I brush my teeth in the stainless steel sink at the end of the bogy, and recall my first Indian train ride, 35 years ago: Delhi to Hardwar, a holy city at the foot of the Himalayas. Blurry eyed, stumbling down the aisle to the toilet, I stopped dead in my tracks. At the washbasin were two naked sadhus wearing only saffron thongs. They had their backs toward me, huge buttocks shaking madly side to side with the train's rhythm. Zealously, they went about their morning toilet: brushing teeth with neem twigs, scrubbing beards, smoothing eyebrows, twisting dreads, applying stripes of paint, crowning their heads with flowers.

Who paid them any attention? No one but me.

∴

14 October, Puri

Wake to 4 a.m. conch sounding from nearby Hanuman Temple. Damp stone, damp odors of dung and boat calk. The first glint of lavender sky brings women up the temple steps, saris flowing; incense, oils, and flowers in tiny brass buckets. After puja they dodge the temple cows and continue down the alley to the beach. At 9, Anita and Sanmath meet us to stroll the breakers and have breakfast. There's a shorefront café, right in the sand; we order lassis, spicy vegetable omelets, fresh papaya, bananas, and coffee. The sea coils and foams. Salt crusts on our cheeks. The inner waters of the body surge to meet the earth's waters. Fishermen ride the waves under triangular sails, the old Arabian sails that catch the wind from any direction (Columbus' square sails could sail him in only one direction). With quick precision, the fishermen maneuver the surf, returning from a "day's" work, though day has hardly begun.

long before

the boats arrive,

scent of fresh catch.

Renée and I spend the rest of the day walking without plan, glad to be in Puri, one India's holiest pilgrimage sites. The Jagannath Temple is on our itinerary, so is Konarak, the 13th-century Sun Temple an hour up the coast. Puri's growth is alarming, most noticeable along the beach. It's not the laid-back hippie retreat of the 70s, nor the kicked-back place of the 90s. Residents claim the town has tripled in population since then. New hotels are everywhere, one blocking another and both blocking the original Sea View Paradise or Ocean Breeze Lodge, where there's no sea to be viewed nor breeze to be caught. Many hotels are unfinished, or finished in a slapdash way. Rebar pokes from sloppy brickwork, garish signs hang from unpainted balconies, sewers can't hold their wastes.

"Things have changed" is the new mantra in Puri. The village of yore is under the mire. Green fields and flowering orchards are beneath the arterial roads, boxboard slums, public housing, and the glass-front offices of corporations who prioritize shareholders and overseas investment, not the locals. My father grew up with the ice wagon and lived to see the exploration of Mars, yet he always said the biggest change during his lifetime was in human relationships: "people have lost their respect for one another." That was in the '90s; now the change has been moved up several notches. The sensible pace of village life is under the dust of a new global upward-mobile crowd operating on fast forward, prioritizing "I, me, my." Human relationships have become marketer-consumer relationships. While seller and buyer pursue their material cravings, they are in turn pursued by stress, worry, suspicion, dissatisfaction, and orneriness. The pharmaceutical industry is having a ball with anti-depressants, sleeping pills, pain killers, and relaxants. The electronics industry, too, is enjoying its plunder, providing "great escapes" for the mired under. Television, the computer screen, the mobile phone; the 21st century's terminal disease is the "stay connected" phenomenon: wherever you are, you can be where you're not. And nobody's going to care. Because they're not there, too.

stepping from her limo

the bride parts her veil

to check her messages.

∴

At four p.m. we meet Anita, Sanmath, and their little girl, Alicia. We hop a rickshaw towards Anita's mother's house in old Puri. Shops in narrow alleys sell handloom silks and cottons, religious paraphernalia, hand-painted seashells, astrological charts, and quirky papier-mâché idols of Lord Jagannath. The crowd begins to pick up, a nervous, trembling sensation. We sidetrack into the craziness around the outer walls of Jagannath's abode. Behind its fortress-like barricades are dozens of mini temples and a massive 24-hour kitchen that serves a non-stop flood of pilgrims. There's a whole population of priests who do nothing but attend the idol of Lord Jagannath, and there are assorted guides, not only for westerners, but for Indian tourists from afar who seem as perplexed by it all as we are.

Nightfall. We peruse the trinket stalls, watch the crowd. The temple's many-tiered domes — breasts, nipples, phallic-ribbed lingams—are lit with colored lights. Across the street, we pay a small fee to enter the Raghunandan Library, a dank centuries-old building housing rare palm-leaf manuscripts. From its flat roof facing the Jagannath Temple, we watch ant-like pilgrims parade into the brightly-lit portals of the inner sanctum. Everywhere sacred cows laze with indifference, casting weird silhouettes on the walls. Juxtaposed with their bony hulks are the bladelike bodies of women wisping along with armloads of flowers, oils, and sweets. Occasionally a bangle, an anklet, a nose ring glints as the women vanish into the blinding light at the temple entrance. Behind them follows the indiscriminate mob, from which stands out a trident-wielding sadhu, a khaki cop, a monkey-like band of ragged mendicants, an upper-caste family glued to cell phones, stepping from a chauffer-driven Ambassador.

From our vantage point — the closest we can get as non Hindus—the temple looks like something from War of the Worlds, an alien ship set down from outer space, round and squat, phosphorescence bleeding from its honeycombed portals. Who knows what goes on inside. Delirium, devotee insanity, spiritual Fantasia, erotic gyrations under hallucinogenic strobes? From here there's only the mystery of the walls, and from behind them a frenzied, psychotic derangement of clanging bells, screaming horns, lewd slaps, bolts of popping electricity, fog of syrupy incense. Suffocation, disorientation. A moist, hammering lunacy. A place where pain, quarreling, caste wars, politics, and family rivalries are temporarily pacified with spiritual anesthesia. It's crazy carnival madness, a very ostentatious public display of worship. Yet, it seems to work, seems to rouse the senses, focus the worshipers on the divine as they reach to sound the brass bell, purify the body with fire, fill the nostrils with nectar.

all that Buddha

rebelled against

still in place.

∴

We find our way down the library steps onto the streets. A parade is in process, profuse with clamor, the volume hostile. A multi-armed deity smiles inside a flaprag tent on the bed of a rusted truck wreathed with tinsel. Smoke spirals from her see-through attire; a sparkling tiara bobs on her matted locks. Following behind her are two rows of brightly-garbed men tied one to another by thick electric cords that light the high-voltage candles they hold at their chests. Slowly they march, like astronauts strung together with lifelines, the wires bringing electricity between their arms, powered by a chugging generator mounted on a jeep bringing up the rear, its tailgate painted with H O R N M E.

On the town parapets are furry silhouettes — monkeys. Exactly human in shape, they perform the same public acts we do: nose picking, hair preening, lice scratching, the dutiful rearranging of balls, the adjusting of breasts to feed the young. An explosion of sky rockets sprays us with sparks. Renée gets slammed into by a sacred cow. Conch shells drone from alcoves. A beggar pokes a finger into my ribs. Crows flap from the stars to snatch the leaf-wrapped offerings left by pilgrims. Sensory fatigued, but in good cheer, we hail a rickshaw and are off

to the quieter lanes where Anita's mother lives.

We're warmly welcomed, served milk tea and a delicious array of samosas and pakoras on plastic saucers — all of us kicking back on a giant bed between the earthen walls of a simple room decorated with bands of painted flowers. A throwback to Pueblo festivities in New Mexico, the spontaneous welcome by strangers into baked mud or cinder block homes, the instant pleasure of coffee, hominy,

and chile. The laughter.

Within moments arrives a relative with prasad, the sacred temple food. Anita sets the floor with banana leaves and onto them places the red and white sweetened rice, fried roti, vegetable curry, sweet and salty dal, a lime-salt-chili side spice, and an unbelievably rich milk-solid dessert. Water is served in a large brass pitcher—brass providing the necessary ayurvedic properties to purify the water. Everything is eaten with the right hand, sitting cross legged on reed mats. Anita says "We're glad to be giving this to you. America has given us so much."

Sanmath describes how Puri swells with a hundred thousand pilgrims each June during Rath Yatra, the chariot festival. "The hotels are packed, every rooftop crammed with people watching the chariots. Jagannath's car is five stories high, the two smaller ones carry his elder brother Balabhadra and his sister Subhadra. Crowds of men pull them on giant wheels with bare hands and ropes. Fanatics, all of them. They dance for days."

∴

In Sanskrit Jagannath means "Lord of the Universe." Jagat/Universe; Nath/Lord. It's the root of the English word Jaggernaut, "unstoppable thing." Hindus regard him as Krishna, an incarnation of Vishnu. Originally Jagannath was a village god; there are many versions of his story, this one pulled from a Michael Castro letter:

"There once was a king who was a great devotee of Vishnu. He prayed hard for Vishnu to incarnate in Orissa to preserve the dharma. One night he heard the voice of Vishnu telling him to go to the ocean and look for a special sacred piece of wood that could be fashioned into a new incarnation of Vishnu. The king wandered by the shore and found a piece of wood darker than he had ever seen, and so hard that none of his carpenters could cut it with their axes or dent it with their chisels. The king didn't know what to do until one day a being appeared who announced himself as Visvakarma, the carpenter who could do the required job on the wood. All he needed, he said, was a room to himself to do the work, and to be left alone and not interrupted for 21 days until he was finished. The king and the queen recognized him as a supernatural being and dubbed him the Celestial Carpenter. They gave him a room and vowed not to bother him. He set to work and the king and queen rejoiced in the sounds of his hammering and scraping through the closed door. On the seventh day, however, no noise came from the room. On the eighth, when there was no sign of activity, the queen became so curious and concerned that she talked the king into opening the door. Visvakarma stopped his work on the spot and vanished. Thus Jagannath and his little brother and sister remain incomplete — physically blockish figures, stumps for arms and legs, and crude cartoonish eyes." The king placed the unfinished figures inside a temple and every year a grand procession was held during which the three deities were dressed in jewels and wheeled through Puri on an immense carriage. To this day, anyone who sees Lord Jagannath or pulls his chariot attains spiritual merit. People carry on a personal rapport with Jagannath in their homes, too, talking to him intimately through a priest, sometimes even cursing him out like they would an irritating family member.

before giving

his blessing, the swami

asks for a cigarette

∴

15 October, Puri

Woke last night with ill effects. It's not India, not the food, not the water. It's the anti-malaria pill. Haven't taken one since Peace Corps days. The effects were weird enough then, but this takes the cake. We were talked into it by an old India hand who warned that mosquitoes would be a problem in Orissa, especially after monsoon flooding. Larium, the recommended medicine, we learn is outdated; the label warns: "not recommended for bi-polar, manic, or chronically depressed people" (what about poets?). Both times we took it we woke with nightmares. Renée dreamed of a best friend shooting up and driving her car over a cliff. I watched fierce-eyed dogs shit in a cathedral while I suffocated between grotesque bodies in the choir loft. Got writer's block? Take Larium. You'll have no trouble with imagery. The final test: you'll either laugh at your dreams or contemplate suicide. We dump the meds and decide our best insurance is a dab of repellent and long-sleeve shirts after sundown. Mosquito net? Too hot; a ceiling fan directly over the bed works just fine.

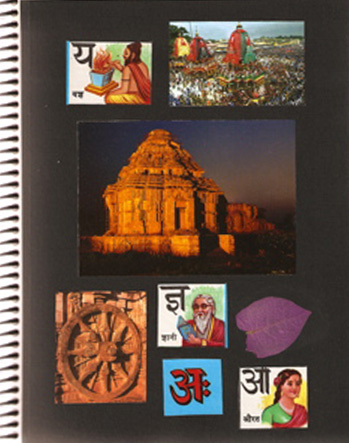

We'll take a morning stroll, proceed to Konarak, then tomorrow take a two-hour train to Bhubaneshwar to explore old Orissan temples. We hope to visit Dhauli, too, site of the 3rd century BCE battle after which king Ashoka embraced non-violence and spread Buddhism across the Indian empire.

On our walk we discover a sandy path to the waves where there's a miniature shrine gleaming in the sun: birthday-cake breast, saffron pennant waving from gold nipple. The mud wall around the shrine is slowly deteriorating at bottom. Along the top of the wall there's a freshly-painted warning:

CLEAN HABITS SHOW GOOD MIND

PLEASE DO NOT PISS HERE

In the bazaar we buy a crude chiseled-wood, raccoon-eyed trio of Jagannath and his two siblings — 20 cents for the three. There's a ladder propped against a clothing store, a sign painter on the top rung painting super-realistic panties, boxer shorts, sleeveless t-shirts, and bras, slowly filling in the slogan:

SKIN FRIENDLY TOP EXPORT

FITS TIGHT COMFORT

We purchase bottled water and etched palm-leaf bookmarks at Cold Goods World Trade Store. When we ask for toilet paper, the owner smiles, takes his last rat-chewed roll from the top shelf, and sells it to us for 15 rupees. I blow off the dust and grumble about the dirt. "Why does it matter?" he says with a frown. "You're going to get it dirty anyway."

On the bridge over the open-sewer river that flows from Puri into the Bay of Bengal, three village women clad in flower-patterned saris meticulously decorate the iron railings with puja designs using rice and unopened hibiscus flowers. When they finish, they fold palms to breasts and pray towards the ocean. I appreciate their devotion, but appreciate more the active devotion by townsfolk to protesting the open sewers flowing into the sea. Puri's officials have finally met their demands. The city is installing underground sewers, albeit there are now complaints that the pipes are too small. Daily, the husbands of women like those on the bridge (we're told they come from Tamil Nadu) dig ditches with crude metal scrapers. A single shovel tied to a rope and hefted by a pair of men lifts the tailings from the ditches.

We say goodbye to Anita and Sanmath. They've certainly laid claim to a wider world, having left Puri to enjoy a new life in America, yet with a strong homeland identity, they've returned to re-establish roots. Just like others we've met in recent travels that tried America, achieved what they wanted, but decided their native lands might hold a better life. Over tea and ice cream we share a laugh about a driver we hired for an excursion to an artisan village two days ago. Hoping to go to America, he learned English, and bragged how good he could speak. "Speaking English 15 years," he kept saying. But that's about all we understood all day long. "We go pissing willage (fishing village)." "No down step latrine use road" (don't step out of the car onto the road shoulder because they use it for a latrine). "Poor guy," Sanmath chuckles, "He didn't know he'd been speaking bad English for 15 years!" Of course, what little he spoke was infinitely better than our Orissan.

∴

15 October, Konarak

Easy ride from Puri along a pretty stretch of ocean, though many of the causarina trees are ragged and broken from the 1999 cyclone. The forest seems numbed, void of its original strength, still in the state of shock. Water's rough, horizon filled with purple salt mist. The few fishing boats that have ventured out at dawn are already in. A lonely, abandoned feeling pervades. Konarak is another story, though. Hoards of Indians are there when we arrive, doing the fast-paced pilgrimage circuit. Only a few foreigners. We are singled out by more than one vacationing Indian family who want us to pose with all the relatives in front of the ruins. We feel like movie stars yanked from one group to another, greetings exchanged, cameras clicking. After the Indian families move on, we escape into the walled sanctuaries.

It takes some settling and adjusting — to the physical site, the tourists, the ornate complexity of stone — before the eye adjusts. The main attraction is the 100-foot multi-tiered stone temple built to resemble a chariot. It rises from a plinth banded with friezes of parading elephants, musicians, rambling flora, and entwined lovers. The chariot, the celestial cart of Surya, the sun god, is at first hard to visualize. We are too close. But when we discover the huge stone wheels— symbols of the solar year — sculpted on the north and south sides, their hubs carved with miniature couples in

erotic poses, it begins to become clear.

In ancient times, the chariot must have been incredible. Seven sculpted horses drawing it toward the dawn. Fire burning under carved deities wrapped in hand-woven cloth. Priests blowing conch shells from the cardinal points. Dancers in the pillared hall. Yogis along the river perfecting mantras to the rising sun. A 200-foot tower rose behind the chariot, but it's rubble now. As is the harbor which the temple overlooked — trade ships docking from all over Southeast Asia. After the river that fed it changed course, the bay silted in. Konarak is now three kilometers from the ocean, but dig deep enough and surely the old port would reveal itself — beneath the trinket stalls and tour booths around the kiosk where you buy a ticket, cross the manicured lawn, and walk into the restored temple.

between the crush of feet

a perfect white blossom

opens to the sky.

∴

While Indian families speed along, we linger before elaborately-carved erotica on the upper level, the kama level, where couples copulate in every conceivable position, arms and legs voluptuously entwined in often impossible poses — sweetly caressing, seriously embracing, giving each other the go ahead with tender foreplay and ribald teasing. A woman raises an arm to remove a bangle, a man fondles the earring of a courtesan, an open palm cups a breast, fingers run through locks of hair, a hand slides down a hip, a toe tickles a toe. A favored place for sure, an altar where male and female join, transfigure, meet the Divine. Quite unlike the altar I knew as a child — all those saints and virgins fully dressed, standing alone,

suffering through their pleas and lamentations.

Here, couples do it under the blue quilt of the sky, an open-air party of unabashed lovemaking where bodies perform outrageous asanas, draw their limbs up, achieve ecstasy while honoring the gods. Konarak celebrates earthly and divine, carnal and celestial. Male and female are not in opposition, but reconciled in delight. A man stands on his head using fingers and cock to please three women at once. A girl hangs upside down from her partner's shoulders, bending backward to suck him while he puts his lips between her legs. A youth takes his girl from behind, her lavish buttocks raised, shoulders arched, head thrust back as she takes another man into her mouth. "Exuberance is Beauty," wrote Blake, and beauty pulses everywhere here. India at its most sensuous — and, for some, at its most shocking. In one not-too-secret nook is a gentleman masturbating next to a youth tickling the slit of his consort. There's always somebody peeking, too; parting the bushes to learn from an adept couple exalting in the playful tingle of intercourse.

boldly grabbing

his waist, the village beauty

half undone, guides him in.

∴

The heightened transport in which one lover dissolves into another and both disappear into a threshold is what Salman Rushdie writes about in Vina Divina. He calls that threshold a state of where "glory bursts upon us and the bolts of the universe fly open and we are given a glimpse of what is hidden; an 'eff' of the ineffable." But how aloof from this state of grace we've become; busy with our separate pantheons, our mercantile and military strategies, our superiorities and petty battles. "Our lives are not what we deserve," Rushie says, "they are in many painful ways deficient." But, he adds, "song turns our lives into something else."